Takeshi Kitano’s Hana-bi (Fireworks) is a masterful symphony of contrasts, a film that juxtaposes serenity with violence, silence with chaos, and tenderness with brutality. As an intricate portrayal of human emotion, it mirrors Japan’s societal condition of the late 1990s—a nation wrestling with economic uncertainty, social alienation, and the aftermath of rapid modernization.

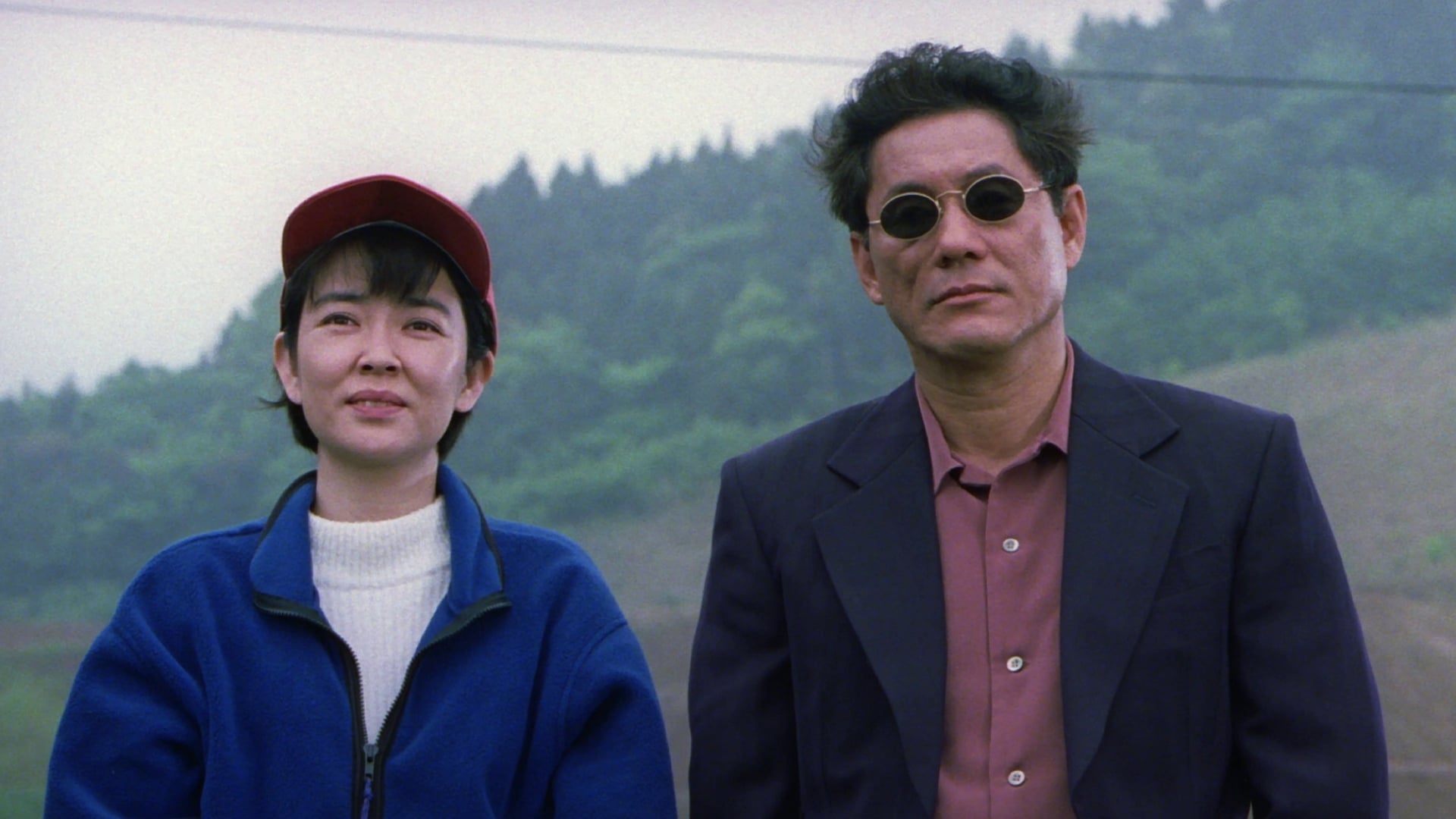

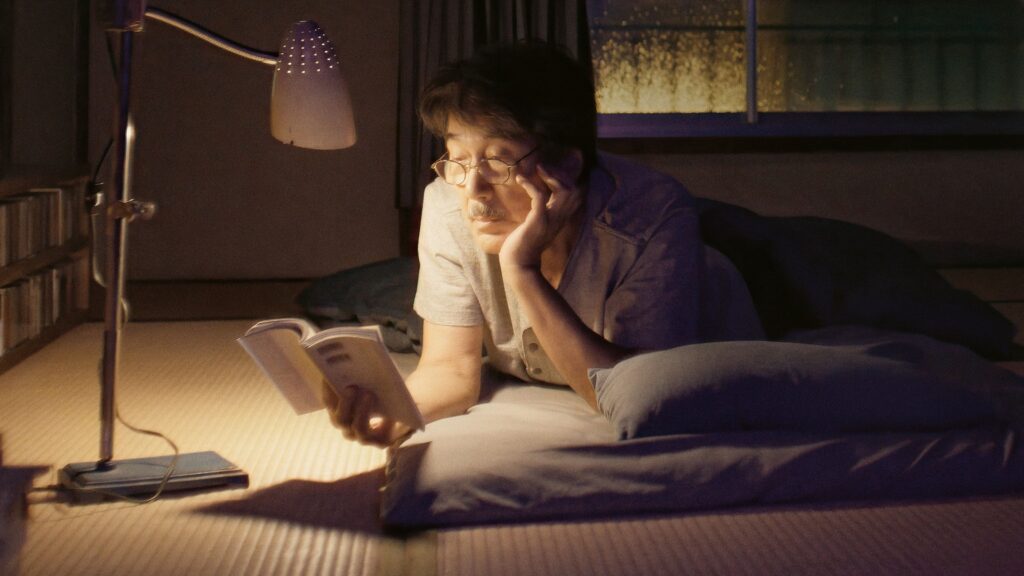

The narrative centers on Nishi (played by Kitano himself), a former detective, navigating a series of personal tragedies—a terminally ill wife, a paralyzed former partner, and his own spiraling sense of hopelessness. What’s striking about Hana-bi is its restrained use of dialogue. Kitano fills the silence with breathtaking moments of beauty—like dreamlike landscapes or solitary scenes by the sea—only to punctuate them with sudden eruptions of violence. This mirrors life itself, where moments of calm can be shattered in an instant.

This tension reflects the disquiet many Japanese felt during the 1990s, as the country faced the bursting of its economic bubble. Japan’s “Lost Decade” saw an increase in unemployment, a slowdown in growth, and a collective anxiety that had been largely unfamiliar in the post-war period of economic boom. Nishi’s silent, internal struggle to reconcile a life torn apart by fate mirrors the quiet despair felt by many individuals during this time—a society that prided itself on stability now found itself grappling with stagnation and uncertainty.

Yet, Hana-bi is not just about despair. The title itself, meaning “fireworks,” speaks to the fleeting nature of beauty and life. Fireworks, like Nishi’s violent outbursts, are both destructive and mesmerizing, offering brief moments of awe before they vanish into the void. This is reflected in the film’s careful pacing, where moments of tenderness between Nishi and his wife are given room to breathe amidst the chaos. It’s an allegory for how love and human connection can persist, even when everything else is falling apart.

Kitano, known for his stoic, deadpan performances, channels a kind of repressed emotion that resonates deeply with the Japanese ethos of gaman—endurance and silent suffering. His character, Nishi, does not express grief through words but through actions, some of which are violent, others unexpectedly tender. It’s a reminder that in real life, emotions are often complicated and messy, and grief can manifest in destructive ways when left unchecked.

At its core, Hana-bi is a meditation on the human condition: how we confront pain, how we seek redemption, and how we cope with the transience of life. In this way, it transcends its time and place, speaking not just to Japan’s societal struggles of the 1990s but to the universal experience of trying to find meaning in the face of life’s chaos.

It’s a haunting and profoundly human film that asks us to look inward—to see the fireworks in our own lives, the moments of beauty that flare up even in the darkest of times, and the way we, like Nishi, grapple with the delicate balance between love and violence, life and death, hope and despair. Hana-bi isn’t just a reflection of Japan’s tumultuous era; it’s a mirror held up to the world, forcing us to confront our own fragility.